The story of Teachers 4 Schools

I’m walking down Rothenbaumchausee, an avenue of mostly 19th century villas that make up one of the most groomed parts of the free and Hanseatic city of Hamburg. Everything is orderly. The trees, linden and chestnut, having turned a lush green with the early days of spring, line the road trooping their colour. The cars that pass, do so quietly, afraid of disturbing the peace. Spotlessly clean, their shiny chassis gleam, reflecting both the rays sunlight and the wealth of Germany’s richest city. If there are pedestrians, I’m oblivious to them as I concentrate on keep my grip on the two old cardboard boxes I’ve been given; they’re splitting with the bulk of the donated textbooks, pens and pencils inside. If there are any onlookers, they will not fail notice my unshaven unkempt appearance. I have miscalculated the heat of the afternoon and dressed too warmly. My shirt is untucked, and my sleeves scrunched up as if ready for a fight. I near Dammtor station and my S-bahn train home, but it looks like I’m not going to make it. Any moment now there’ll be books, pens, pencils, all over the place. I want to curse it all but stop. “This is just the beginning,” I remind myself: in just a few days I’ll carry these same books and probably more, through the streets of a much hotter, noisier West African sprawl. I almost crave its anarchy now. “This’ll be my penance” I tell myself, but for what, I can’t decide, and look on.

Yesterday, on a whim, I sent out an email to friends and colleagues asking them to donate materials for ‘a school in Africa’. Which one and where? Luckily nobody asked. I didn’t know! It had just seemed like a good idea at the time – this is how many of my adventures begin! I’d been invited to go to Senegal to give a talk at Africa TESOL, a conference for English teachers from across the continent but as I would be there for less than a week I would be travelling very lightly. That was what had led me to come up with the idea of using up my baggage allowance, by collecting enough school materials to fill one of those huge suitcases that just took up space in the cellar and bring it along.

The first to answer my plea was George at Intercom, a very popular language school in one of those villas I mentioned. She’d posted something in the HELTA (Hamburg English Language Teaching Association) Facebook Group asking for suggestions for where to donate old books. When I suggested lugging them across to Africa, she invited me over immediately.

“It all starts here!” she said as I set out from her building onto the street the next day, grasping two full boxes of what I thought might be appropriate: a whole series of Headway and In-Company, a Wallace and Grommit video, something about writing business emails… George was right, it all began there on 25 April, a las cinco de la tarde!

“Are you going to the Gambia?” asked my trusty friend Wilton Mills “I know someone there!” And that’s how I got to be in touch with Alhagie Fofana. As I found out much later, Wilton didn’t just ‘know him’, he also happened to have funded this Gambian’s complete education and healthcare since he was an ususpecting little child in a rural Gambian village. This allowed him to eventually qualify as a state nurse. Now, as a consequence, at 35 years old, a grateful Alhagie says he is able to pass on that kindness and take care of his own family.

Looking at the map, I see how small the Gambia is – a tiny land, the smallest in Africa, that slithers along the River Gambia.

“It’s a tongue!” says Yusuf, a student in my ‘immigrants’ class at Berufliche Schule für Medien und Kommunikation (BMK to its friends). He’s from Serekunda, an urban sprawl near Gambia’s capital, Banjul. He has a point. Looking at the county’s profile, I can see it looks just like the Atlantic Ocean is sticking out a Snoopy like tongue at an indifferent, vast land mass. Other than its coast, Gambia is completely surrounded by Senegal.

“It’s perfectly do-able!” Yusuf continues “you can go there from Dakar in eight hours.”

I check Google Maps and see that a round trip would be about 600 km. “It’s nothing!” he reassures me. After crossing the sea from Africa to Italy, Yusuf had walked the rest of the way to Hamburg.

“How long will you go for?” he asks.

My answer seems to pain him. “Two days, maybe three!”

There is a momentary lapse of reason.

“Yes, but you can do it… if you want!”

“ But is it safe?” I ask. Many have since asked me the same question – first world stereotypes die hard. “What about Boko Haram?”

“They are not there. Christians and Muslims live very peacefully together in the Gambia. It is very safe, but be careful, when they see your white skin, they will find ways to get money out of you!”

With over a third of its population of 1.7 million surviving below the United Nations poverty line of about a Euro a day, you can hardly blame them.

Money was a sore subject right now. Just a couple of weeks earlier my credit card had been blocked by the bank for no good reason other than it had been hacked, and my bank, whose name shares an adjective with the country, was making no effort to get me a new one anytime soon. When Jim Faulkner came to my office to make a donation, I was in the middle of a call to its help-desk, whose operatives, strangely, all seemed to be South African. When I had mentioned that I need the card to go to Africa, they had taken a vested interest and asked inappropriate questions. They were very sorry but there was nothing they could do to unblock my credit card, ever! Appointing him on the spot to my Rechtsanwalt, or lawyer, I passed Jim the receiver and asked him to find out why. Try as we might, there was nothing we could do. I would have to travel with cash, to the place that Yusuf had warned would ‘get money out of me as soon as they saw my colour’, even the Foreign and Commonwealth Office website had warned about the notoriety of pickpockets in this region.

“Why are you doing this?” Jim asked.

It was a good question and also one that I hadn’t yet thought about.

I could have said something about how I cared about people in under-developed areas, how I admired the likes of John Lane in Gibraltar, who I met just before the war in Darfur had started, busy loading up his truck with medical supplies to drive through Sudan. Or how, Alma and I on our recent visit to Uganda, had met an Italian lady at the Equator, with two children and some huge suitcases. “We try to visit a new African country every year” she told us, each time they did so they filled a big suitcase with urgent supplies for the locals. But if I was 100% honest with myself, it was probably not their benevolence that I admired most, but their adventures that I envied.

When we said goodbye and were leaving the area, satisfied that we had achieved our tourism goal, we drove past children working in a nearby stone quarry. Still I only wondered what we could do. Another cog in my wheel, came unexpectedly on the streets of Masaka, a large town on the banks of Lake Victoria. I had spotted some huge fruit for sale along the drive here and was keen to try some. I found out that it was called jackfruit, so I approached a lone teenaged girl sat on the pavement selling slices of this juicy flesh to passers by. To wrap the fruit, she tore a page from a book, and watching her I realised she was tearing pages from her old school book. A hopeless education, I thought. As a teacher myself, seeing that affected me profoundly. This was also when we met that Italian lady. Rather than thinking I could do something, I felt I had to, and more importantly, I wanted to.

Before I could tell Jim about any of this, Rebecca Garron arrived with her own childrens’ books and a big wooden puzzle. I’d told everyone I knew that ‘little things make big differences’ and their response had taken me by surprise. Over the remaining few days in the lead up to my flight to Dakar, several stopped by my office to give what they could. Some shared my message on Facebook, my friend Barbara Reitmann at the BMK, had made sure that all my colleagues knew and they were pleased to clear things from their offices. Even my own students brought things to take. I’d asked for pens, chalk, books, games, paper, a list that Didan had helped me prepare. Others made donations. With these, I went out and bought a whole bunch of pretty note books, games, and recognising the importance of music, even a pair of tambourines. I had so much I had to get one of those nifty suitcase scales to measure it all to see hoew much I could take. I had 45 Kg.

Before I could tell Jim about any of this, Rebecca Garron arrived with her own childrens’ books and a big wooden puzzle. I’d told everyone I knew that ‘little things make big differences’ and their response had taken me by surprise. Over the remaining few days in the lead up to my flight to Dakar, several stopped by my office to give what they could. Some shared my message on Facebook, my friend Barbara Reitmann at the BMK, had made sure that all my colleagues knew and they were pleased to clear things from their offices. Even my own students brought things to take. I’d asked for pens, chalk, books, games, paper, a list that Didan had helped me prepare. Others made donations. With these, I went out and bought a whole bunch of pretty note books, games, and recognising the importance of music, even a pair of tambourines. I had so much I had to get one of those nifty suitcase scales to measure it all to see hoew much I could take. I had 45 Kg.

That response convinced me that what I was doing was right. Initially my only draw to the Gambia had been a ‘because it’s there’, but seeing how easy it was to use my influence to pool the people I knew to collect donations and support, no matter how big small. I realised the potential of changing a lot of people’s lives. When I shared this experience with some friends who were also teachers, they agreed we could make a difference. Pete Rutherford, who had travelled extensively in Africa and knew what I was up against, Wilton Mills, a dark horse who has done more for others than he would ever admit, Helen Waldron, who was recognised for ‘sticking up for social justice’ agreed to join me in what I’d call ‘Teachers for Schools’.

Just days later I walked out of Senegal headed for the Gambia, followed by a man, his donkey and the cart which my suitcase lay on. Teachers for schools was going wonderfully. I had received so much that, even when exceeding my total weight allowance and stuffing pens and materials in my pockets (had anyone picked them they could have started a school) to get onto the plane from Hamburg to Dakar, I had had to leave things behind.

In Senegal, I had gone all the way to the Gambian border by minibus and taxi. The road was not particularly busy or rough, but it was so so hot that I passed out several times along the way, no longer sure of what was real and what was dream. Though the journey was no great distance to speak of, it was slow. The road had regular speed bumps, three times as high as those I was used to. For most of that journey my case remained strapped to the roof of the vehicle with other baggage, and on top of it all, a man to make sure it stayed in place. Each time we went over one of the speed bumps, if a bit too fast, I heard him scream to remind us he was still there, only this time accompanied he was accompanied by the rattle of a tambourine. That man, and the man with the donkey were just one of many that had been happy to help for a small tip. Once I had been reluctant but then realised that the 200 West African Franc tip that they wanted was about 30 European cents. In return, I had hardly had to touch the case at all.

I had agreed to meet Alhaji on the Gambian side of the border, and he had since been busy arranging visits to schools the following day. When Senegalese immigration stamped my passport goodbye, I didn’t even have to queue. Then everything changed. At the Gambian passport office, I was told that I did not have the right paperwork. Since I had left Germany yesterday, a new law had come into place stating that I would need my medical certificate.

‘They WILL find ways to get money out of you!’ Yusuf had said and I was not prepared to pay the 200 USD fine that I was now so kindly offered. I faced turning back in my tracks, with nowhere to go. My pale skin and a suitcase that jingled like Santa’s sleigh each time it moved, I would hardly be inconspicuous even in the dark. And, I noticed, those handy little wheels on the bottom of my suitcase had got clogged with sand from the road and chosen this moment to break.

Literally as well as figuratively, I had to see a man about a horse! He and his donkey had been waiting patiently to proceed but now I had no alternative but to retrieve my luggage and pay him.

‘Fifty dollar!’ he said.

Once again ready to curse, I stopped again with bated breath.

‘Wait!’ I said. It began to dawn on me. ‘Fifty Gambian or fifty US…’

’Fifty Gambian Dalas!’

I got my phone out and made a quick calculation. Eighty five of our Euro cents! So the immigration official wanted… to give me a fine for… three Euros and forty cents? I went back and apologised. Of course I would be happy to pay the fine!

On the move once more, I went to look for Alhagie. He was no-where to be seen. So I went back to the same immigration official once more, to ask, if perhaps, I might use his phone. Now he was very accommodating. Satisfied with his loot, he asked for no more money. My friend had given up waiting and was already on the ferry back to Banjul. I should wait for him here until he came back. Our misunderstandings behind us, Gambian immigration and I were now the best of friends. They gave me a chair so that I could sit and watch the proceedings of the border. They asked the inevitable football question, and rather than admit to the disgrace of not being the slightest bit interested in football, I gave them the ‘Ipswich Town, fair-weather fan’ spiel. It is very well rehearsed. When Alhagie, himself a Manchester United fan, eventually did make it back to collect me, I was very pleased to see him. ‘Get me out of here!’ I said. Another taxi, a ferry and a private car later, I collapsed on my bed at the Rainbow Beach lodge.

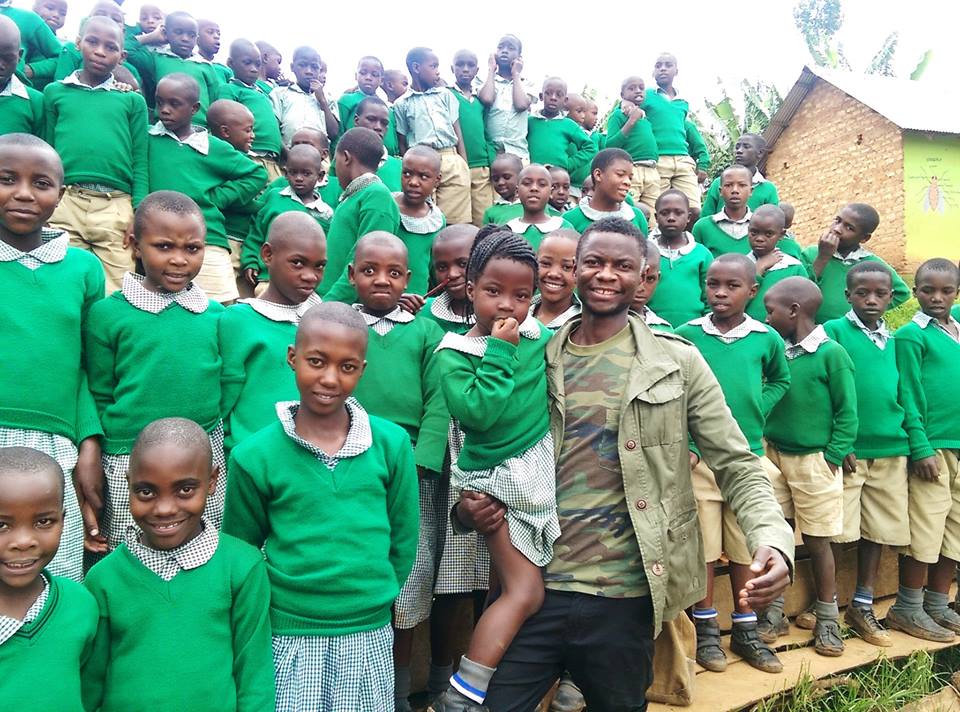

The next morning we set off in a taxi to the first school, the Tujereng Lower Basic School, in Tujereng village. It wasn’t long until we left asphalt behind and drove for some time across sand to get to our destination, where we were received by the Head Teacher, Mr Fadera, an older gentleman who despite being surrounded by very excited children, very relaxed. I started to shake the hands and say hello to each and every child. “We have one thousand and sixty five pupils here” Mr Fadera told me. I stopped shaking hands.

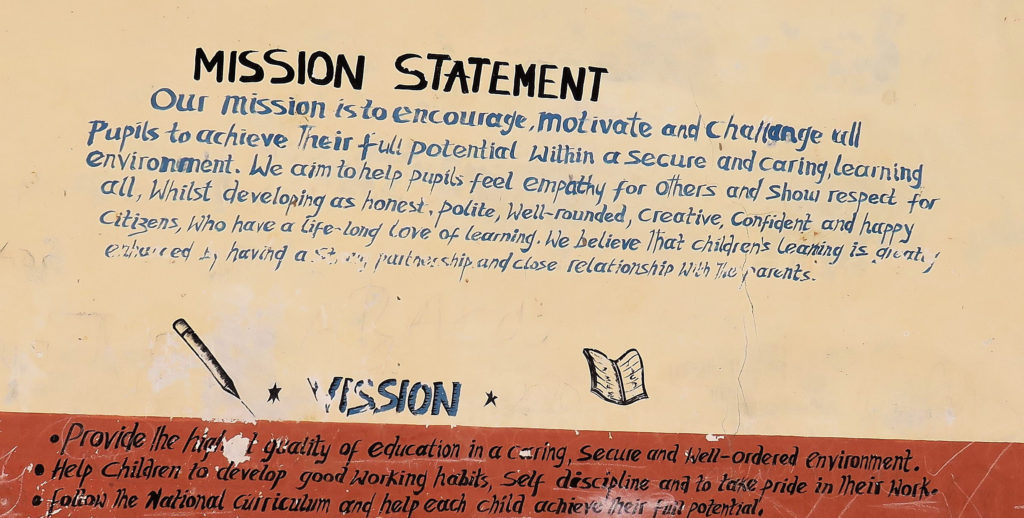

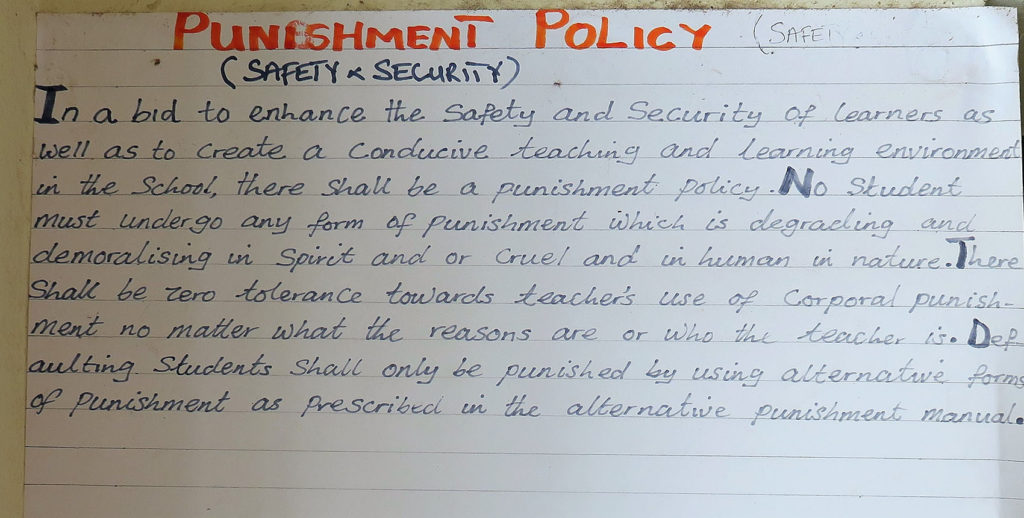

The kids were between six and ten. The school, the size of a small town primary school in the UK, was much older. Built in 1959 when the Gambia was a British Crown Colony. It looked like nothing much had changed since then. Some classrooms were out of bounds because the rooves had caved in, while those still in use looked decidedly dodgy. Their ceilings, a single layer of asbestos cement supported by frail wooden beams so eaten by woodworm that I feared even touching a wall would lead to devastation.

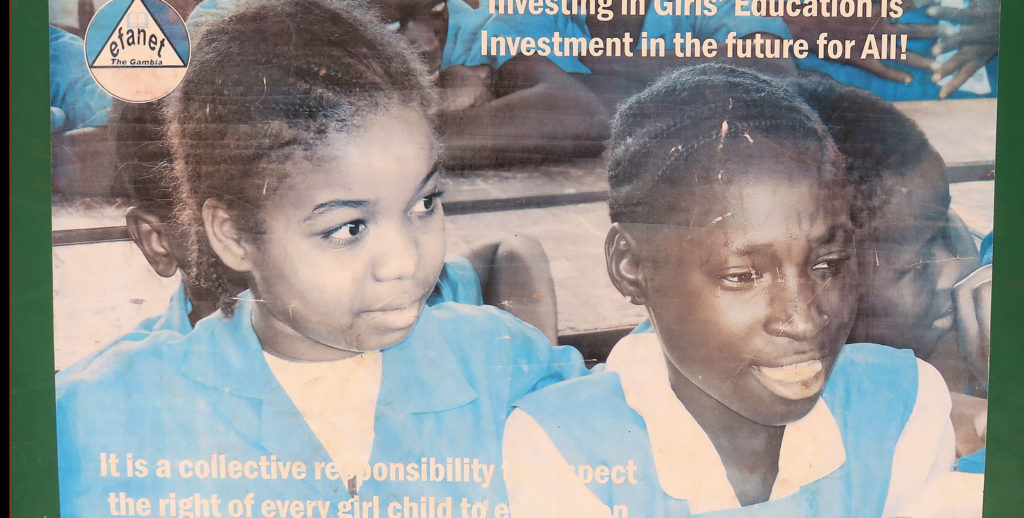

“Attention is a big problem” Mr Fadera told me. Not because of any modern hyperactivity disorders, but simply because of the children’s way of life. “95% of them come from poor families and broken homes. After they have walked to school, many of them are already tired when they arrive, and often they don’t eat until they come home at night.” For the thousand children, there was just one source of water and just two sorry toilet cubicles.

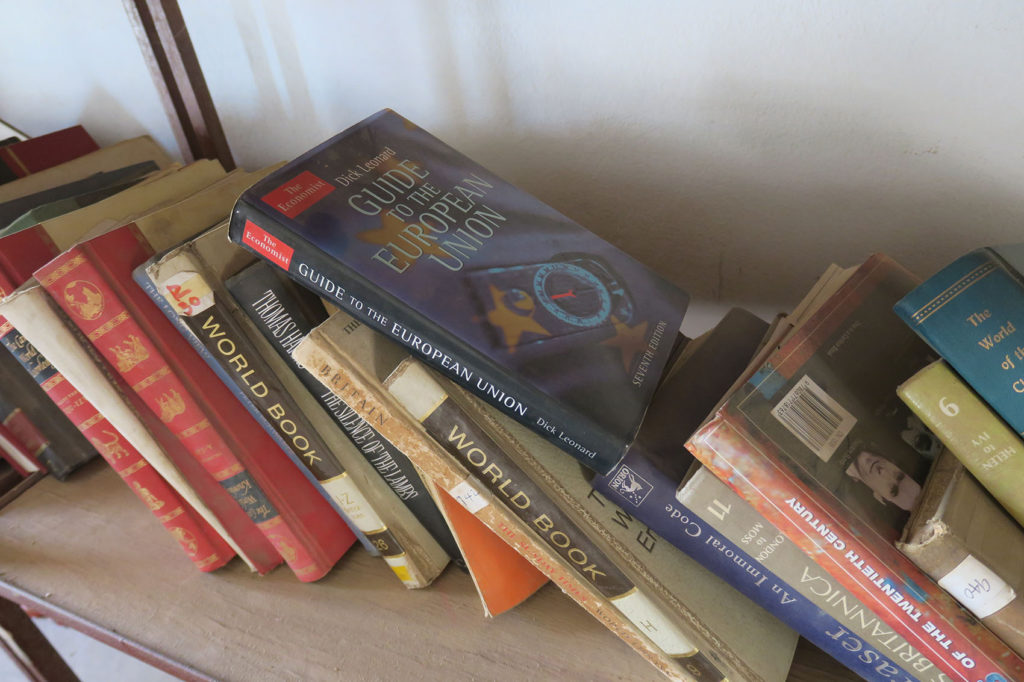

I visited several classes, one of them was using tin cans to learn about volume. The curriculum included English language, mathematics, agricultural science, history and religion (Islamic studies and Christian religious knowledge). The school library, a paltry collection of books, was small and messy, its books as worn as the beams of the building and had probably sat there for just as long: a full edition of World Book from 1964, another entitled Science in the 1970s – I had worried that my copies of Headway would be a bit outdated!

Then it was time for me to present my gift – suddenly the case that I had dragged from Europe, seemed very small indeed. As we opened it, Mr Fadera looked at each item, telling me how useful it would be and expressing his gratitude for it. Before leaving, I recorded a video of Mr Fadera giving a personal message to Teachers for Schools. Our first mission had been accomplished.

By loading the video, you agree to YouTube's privacy policy.

Learn more

The second school that Alhagie and I visited that day was a secondary school in the same village. It too had its fair share of problems: there were old computers but no, or very poor, wiring and its headmaster told me, there was a lack of lab equipment for their chemistry and physics classes. Despite all of this, it seemed to be doing OK with the limited resources that it had, and the fundamental problems of the first, such as water, hygiene, sanitation and food were hardly mentioned.

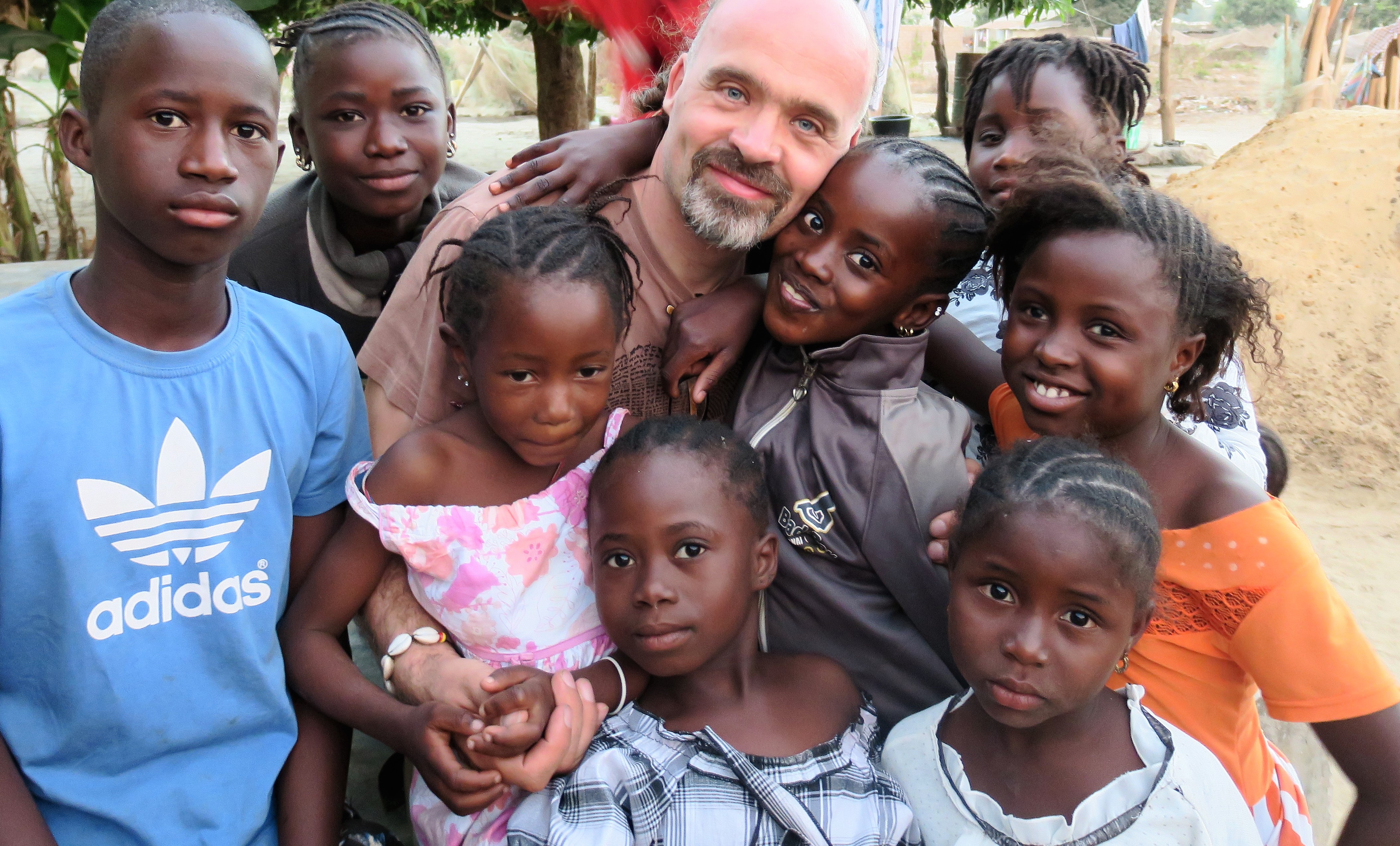

On the evening before I left the Gambia, Alhagie invited me back for dinner at his brother’s home. As soon as I arrived and clambered out of the car, I was immediately mobbed by children. They had my absolute attention for the whole evening – we talked, sang, and played clapping games together. Though it felt like I was there for a short while, it had got dark, we had eaten, and the men had disappeared several times to answer a distant call to prayer. I was later told we were there for six hours. There is a wonderful reward for sharing with others, whether it be monetary, practical gifts or simply attentiveness.

On my way back to Senegal, I shared a car with two giggling catholic nuns on their way to a mission; another lady and her husband, our driver. His character made him seem much larger than life, a loud and extremely funny man. As he speeded us off to Dakar, he introduced himself as Mr Jallow, but told us that he ran a security firm called Uncle Sam. We could call him that if we preferred. He entertained us all for much of the journey, telling us animatedly while keeping one eye on the road. Although a Nigerian Muslim, he told us about his happy childhood going to church and learning about Jesus. He was genuinely interested and respectful of the sisters’ faith, and asked them many questions, making fun of himself in the process. He too happened to be involved in some voluntary work for people with kidney diseases, and like Didan and Wilton did not elaborate.

‘Kidney diseases are becomming a real challenge’ for the Gambia,’ Alhagie later told me ‘and Uncle Sam Security creates many jobs for Gambians’. Though careful to keep my beliefs to myself, in Mr Jarrow’s car I felt completely relaxed and enjoyed taking part in the banter. When we separated hours later, everyone had already agreed to meet for the return journey and I was sorry that I would not see them again. Where else in the world could this have happened I wondered.

I returned to Dakar convinced that Teachers for Schools could work. Most importantly, it would be on a grass roots level with a direct and very personal contact with schools. At the Africa TESOL Conference, I discussed the idea with my colleagues and their suggestions were equally inspiring and useful. Other teaching associations, such as TESOL France and TESOL Spain, are doing some excellent work too, and when it comes to projects such as these, there can never be enough of them, and we should not let politics or religion get in our way.

The best and most productive part of my going to Dakar, however, was meeting Sameh Mazouki, a DELTA qualified Teacher Trainer based in Tunisia. I attended her ninety minute workshop but where she showed us all how to make a data projector out of a shoebox. There were so many more ideas, for improving classroom environments so that learning could take place fast, that I could not keep up. Then she told everyone that she would be willing to go anywhere in Africa to train teachers and I immediately thought of Didan. When I returned to Europe, Teachers for Schools started a crowdfunding campaign to send Sameh to Loving Hearts Primary School. Within just three days we had raised 1000 EUR for her flights to Entebbe, proving that if we look hard enough, there really are some loving hearts out there. The campaign now continues, in the hope that providing the funds not just for Sameh’s flights but for her to do what she does best, we can make a big difference.

Back home, I remove the money belt that I had secretly worn for the entirety of my trip to hide all that cash. I feel very silly. Not once had I felt in danger, even the incident at the Gambian border had turned into one of hospitality and good experiences. Those that had tried to get money out of me had been contented with very little, not once making me feel as though I had been cheated. “What was the Gambia like?” my friends ask me. “The people!” I begin. “The people were so wonderful!”

Andreas Grundtvig

27 May 2018

Help us to help them: https://www.gofundme.com/teacher-training-for-loving-hearts

A free downloadable book of classroom activities for teachers can be found here: The_Words_About_Us_-_Andreas_Grundtvig

Teachers for Schools are: Andreas Grundtvig, Alhagie Fofana, Wilton Mills, Peter Rutherford, Sue Annan, Jennifer Taylor, Rebecca Garron and Harry Kucha.

* Special thanks for to the following for your support, help and donations before and during this trip: (alphabetically) Alhagie Fofana and family, Atukunda Didan, Barbara Reitmann, Birte Blunck, Dörte Mansen-Holstein, George Arping, Jim & Jane Faulkner, Lisa Burchard, Maren Ziesmer, Rebecca Garron, Susanne Stauga, Valerie Alt, Wilton Mills Yusuf Manka, and to all those who donated to the Crowdfunding campaign to support Sameh’s visit to the Loving Hearts Primary School.